Thoughts on a “solution” to the climate problem

19/09/2013

Our Grandkids’ future: some thoughts on a “solution” to the climate problem.

I began noticing the issue of climate change in the first years of my retirement, and around the time my first grandchildren were born. A couple of years after that, after reading Tim Flannery’s book, I knew for sure this was a very big problem - something one ought to learn about and help to remedy. As I’ve become more familiar with the details since then, one thing has been very hard to understand, and it still is - the nonchalant response of the world’s people to this alarming news.

Without a shred of doubt, climate change is a massive, urgent ecological problem, threatening the well-being of all humans, all their descendants for many centuries to come, and all life on Earth. The people in a position to diagnose it for us, the scientists, have been as clear as they could be about this ... we could not possibly have missed their warnings - nor have we - surveys of educated populations consistently show that people are aware of the problem and fairly concerned. But anyone from another planet watching us would surely think otherwise - it is just as if we do not know what we certainly do know; we haven’t done much about it, and we seem to be laying plans for the future just as if there were no such problem at all.

I used to think this was mostly the fault of various groups and individuals who have efficiently propagated misinformation: “merchants of doubt”, as Naomi Oreskes called them. But now I’m inclined to think that although they played an essential part, these folks succeeded because we were somehow complicit in their designs. In some sense we were duped willingly. It was always going to be easier to motivate inaction than to provoke an adequate response from our institutions and collective will - just as if we were predisposed to sleepwalk deeper into this crisis until its effects become overwhelming.

If this is true, it changes everything for anyone like me who wants to see us start on a fix right away so future people won’t have to struggle with our wreckage. It means the goal of overcoming resistance with a powerful popular movement might be fanciful - it might turn out that human societies just don’t have it in them to rally around a threat so insidious, huge and unprecedented. Maybe the degree of alarm needed to activate solutions just isn’t possible for creatures like us, evolved as we are to respond to immediate, visible, identifiable threats with known antidotes. Evidence can be found for a such a view - in historical studies of human ecology; in social anthropology and psychology. This must give us pause.

*****

It’s been said that the climate problem is not a “problem” at all, but a predicament. That is, we shouldn’t be seeking solutions to it, but accommodations. Coming across this idea for the first time, I was both intrigued and a bit repelled. Why would anyone with grandkids think like that? I wondered. Isn’t this the same as abandoning them? Shouldn’t all the folks who care be striving, hope against hope until none is left? Isn’t this a struggle against ignorance, prejudice, power and greed? Isn’t it about turning a page of human consciousness - opposing rapacity with an ecological view of our affairs - of returning the human world to its place in the habitable universe?

Well, here’s the thing … despite these objections, it looks as if this way of seeing things might be correct after all. Here’s why. When we speak of a problem, whether it arrives inadvertently (like the climate one) or through malice or error, or ill fortune, we mean a state of affairs for which we can conceive a remedy. It’s fixable - at least in principle. But other things - say, the existence of earthquakes, or human aggression, or mortality - are different. They can be framed as problems - they frequently are - but not very profitably. That’s because they are more like the terms of existence - irreducible conditions of our life on Earth. We can tinker with their contingency perhaps, but without really changing the facts … we share with every other living thing this basic relation with the world, given once and for all by the nature of things, that no amount of ingenuity or determination can reduce much if at all.

This is no matter for regret, at least for people with a healthy outlook, although it affronts hubris, and for that reason is often rejected. We certainly didn’t create the climate problem by any kind of mistake - that is, we didn’t foresee, then fail to avoid it. No, we brought it on in the tragic manner, by the exercise of normal exuberance, inventiveness, avarice, and so on, all unknowing. Being the sort of creatures we are, we don’t knowingly inflict suffering on our loved ones, our immediate descendants, or even innocent inhabitants of a remoter future. But we can certainly do those things while unaware, and discount the interests of future people. That’s what has happened.

In fact, given the way we are, it’s inconceivable we could have discovered the fossil fuel bonanza and done anything very different. Humans exploit resources, whenever they get the chance, exactly the way every other organism does - by maximizing our biological opportunity. No record exists, anywhere, of a human group governed by prudence rather than satiety, when both are available. You might object that societies in the past have deliberated their way to a sustainable ecological balance - and that is true. But they only did this after first inducing an emergency. In each successful case we know of, adapting to ecological limits followed a painful, involuntary confrontation.

How does this help us understand the climate problem? Well, as Tim Flannery said at the end of his book, we are the first human group ever to have faced an ecological crisis with the capacity to diagnose it accurately and figure out what to do. In this respect, at least, our predicament is different. That means we have an opportunity no other society ever had - to look straight at the emergency and decide to change course before it gets bad. This has never been done before, so we don’t know if we can get organized enough. But we know with great clarity what will happen if we don’t make the attempt; we know we can do it if we really want to; and we know we can’t mess around because it’s urgent.

But so far, we haven’t done anything like what’s needed. If you look closely at what’s actually happened, you’d have to be a bit worried, because it looks very much as if we’ve done about 100 times more talking than we needed to do, and only resolved on some baby-steps that would be OK if they were to begin escalating and sufficient actions ... but they are not. The last 30 years we’ve been just like a patient who says “I know I need the cancer cut out, but I’ll just have a massage instead”. How can we understand this perverse result? Must we impute suicidal folly to our species?

Many people think so. There are a few different ways of saying it. There’s the “we’re hopeless”, misanthropic way - it really means everyone else is hopeless; this is solipsistic and false. There’s another way you hear from folks who vaguely see a climate catastrophe as a kind of Armageddon - inexplicable, but ordained, and acceptable. And there are the people who just can’t figure out why we are not rational when we need to be. That was me when I began this interest, and I still find the idea very tempting. The thought is like this: No one wants their grandkids to suffer, so if only everybody knew what’s going on we’d become an irresistible political force. But I’ve come to doubt this formulation now, having come across two lines of evidence suggesting that this will never be the path we tread.

*****

A few years ago the great California polymath Jared Diamond wrote a book explaining why it is that the modern world has been dominated by European ideas, habits and economic power. Guns, Germs and Steel was a bit unusual. It’s been on bookstore shelves ever since, still selling steadily; read by thousands who never encountered ecological history before, it is a long popular science essay and also a considerable work of original research, crossing the boundaries of several disciplines and addressing some of the trickiest questions in the social and political sciences ... and providing very interesting answers and suggestions that have provoked lots of discussion and debate.

The author followed up with a second book on the related question of why some societies of the past failed and others succeeded. Addressing an old puzzle that’s fascinated historians since the fall of Rome, Diamond gives readers an ecological theory of social development and decay, consonant with the big thesis of his first book. Running beneath them both is a very big idea indeed ... the idea that the human world - the one we invent and create with our culture, language, imagination, economic and social institutions, amusements, constructions and conveniences - the one we devote most of our awareness and energy to; the one we live in - has no autonomy of any kind, but is a sub-system of the dynamic planetary surface.

Stated like this, the idea seems banal, or perhaps trivial. What makes it important is that it’s one of those we can recognize and ignore at the same time. Or rather, we know it when it’s pointed out, but otherwise act just as if we didn’t. Civilized life and invention has provided us with environments so compelling that we can and do live in them exclusively, as if everything non-human on the planet had been put there only for our profit and enjoyment. Without reflecting, we act as though all things on Earth revolve around human interests and concerns. When we look out, we see a world made for us.

Diamond’s work is a sharp corrective to this comfortable view of things. It tells us that all human projects and all conceivable ambitions are eventually constrained by one simple and irreducible fact - humans (and every living thing) inhabit a finite planet. Not only that, but the Earth’s living skin - the biosphere - is a remarkably unified thing. It has myriad distinguishable parts, but they all grew together, constantly changing, during the whole long history of life on Earth, and they interact and depend on each other in ways so complex we’re only beginning to understand them ... and this interdependence is absolutely necessary. Nothing in the biosphere works properly on its own. If these webs get broken, consequences cascade in all directions.

Now it seems to me this is a very important insight - often pointed out, and just as often forgotten. I was puzzled by this amnesia until I remembered something about human cognition that Robin Skynner explained. We spend our time, he said, in one of two states: “focussed mode” and “open mode”. The first of these states of mind is characteristic of us when we are concentrating - say on a task or problem or any foreground concern at all. It’s a bit like going around with your eyes down. The horizon is close; all attention is contained ... it’s as if we shrink the world in order to get things done. This is typically the way we live in the “human world”.

The other mode can just as well be called “receptive” or open or “unstructured”. In this mind-state we are open to the flood of sense perceptions. Rather than processing stuff from the cerebrum, we are admitting and responding to stuff from outside ... not necessarily for any human purpose, but because we are conscious agents of the biosphere. Everyone knows what this is about, but, as Skinner pointed out, we (specially people of the Western culture) have learned to be really good at doing the first mode, and almost forgotten the second. Our life in a global civilization is so enormously complicated it demands most (maybe nearly all) of our awareness in focussed mode. We’ve lost most capacity to be open and receptive - in other words, to know the web of life as our one true home.

Addiction to the focussed mode is often called “hubris” - the delusion that humans can run their affairs however they wish, solving every new problem with something clever; passing every limit by a new discovery; refashioning the place at will. But if I understand Diamond’s message correctly, this behaviour of ours isn’t all pride and blindness, it’s also an expression of something in our nature - something we couldn’t do differently without being a different kind of creature. In this sense, and this only, it is a tragic predicament. We can be conscious of our folly and unable to break out of it.

*****

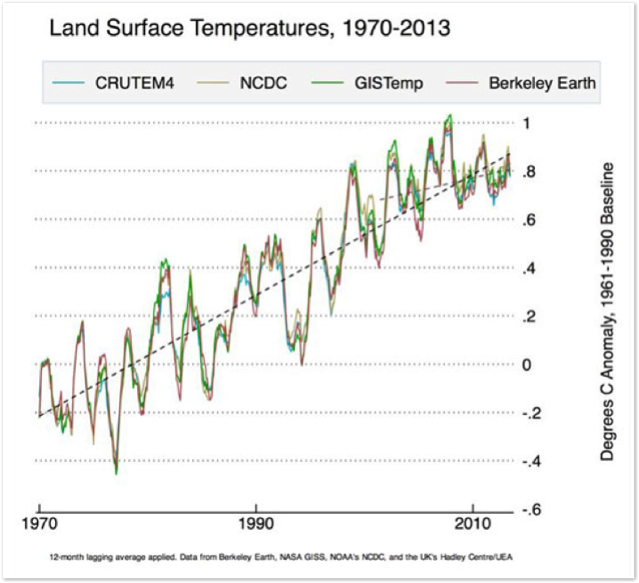

Nobody really knows how hot it will get this century. Let’s face it, when the decade-scale warming rate declined from about 0.15℃ per decade to 0.1℃, as it has done in the last decade or so, scientists had to admit they had no prepared explanation. It’s likely that some combination of natural and anthropogenic variables are responsible and that, in the presence of persistent positive energy imbalance, the planetary surface will resume warming at the old rate some time soon ... but we don’t know for sure. What we do know for certain is that the greenhouse forcing continues to grow, and so prodigious amounts of heat are accumulating in the ocean (Jim Hansen’s vivid description of this quantity is: energy equivalent to 400,000 Hiroshima bombs every day). Sooner or later this will warm the air and ocean surface, and melt the great ice sheets.

Change in decadal warming rate, year 2000-2013

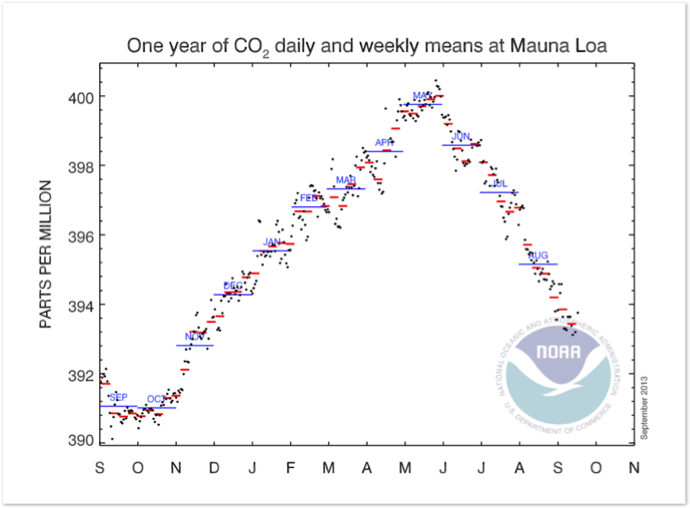

The Mauna Loa observatory in Hawaii recorded 400 ppmv for the first time, for a few days in May 2013. By 2016, the global annual mean will be over 400 - the first time this has happened on Earth for at least 3 million years, maybe more. The observatory also recorded the biggest annual rise in mean CO2 since the unusual El Nino year of 1998 - 2.66 ppmv, the second biggest increase for a single year since records began. Everywhere on the face of the planet, oil companies are exploring and extracting the last accessible deposits in more and more difficult places. It’s very obvious that the age of cheap, easy oil is over. Everything left now is a lot harder to get from the ground and turn into useful products, and much more expensive. In view of the threatening climate problem we could respond to this situation by switching our energy system away from fossil fuels over a generation or two, while the last of the easy oil is used up. But we aren’t.

Daily CO2 reaches 400 ppmv for the first time

Instead, the melting of the Arctic, the clearest possible alarm warning we could have, is being treated as an opportunity to prolong the fossil fuel age as long as profits can be made. If we are puzzled by the Easter Islander who cut down the last tree, then surely our descendants will be just as dismayed by the oil man who drilled into the thawing permafrost until there was nowhere else to go. If they said we were foolish, they’d be right. If they said we were greedy, or blind, or disorganized, apathetic or selfish, they’d be right too, wouldn’t they?

Certainly, we have all the human frailties, as well as creativity and power, and all of them have a share in compelling us to our fate. Soberly assessing the facts, and comparing our behaviour to what it might have been, you must know that the climate on Earth will be different for a long time because of what we have done, and it’s too late now to prevent lots of damage. But the game is never over. Human affairs have always been contests between actors who see different things. Tim Flannery’s claim is still true ... knowing what we do, we can choose to be planetary citizens, fellow creatures of the living Earth, the clever species; or we can draw our horizon close and exploit some limited domain. Some of us will do one, some the other.

I can’t see our future any clearer than this. I often feel an agitated kind of regret when I think of my grandchildren - very much like the kind of anguished helplessness everyone feels when you can’t remove trouble from a loved one. Sometimes it costs me sleep, other times it tinges the joy of their presence. I used to feel something else tagged onto it - something like guilt ... that I had a part in causing their problem; that I couldn’t do more to fix it; that their innocence would be assailed this way. These days, I think I can see the regret properly belongs to something we could never have prevented - the trajectory of human presence on Earth in modern times and the consequences that will entail. Beyond regret we do have one important choice to make - to inhabit the whole world, giving to it the benefit of our unique sagacity now that it is needed most urgently.